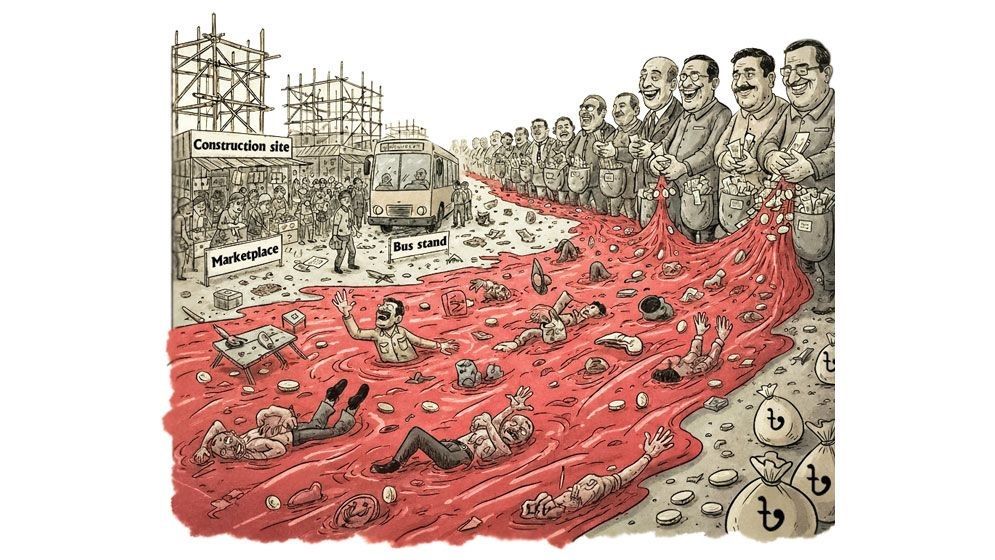

Unstoppable extortion under political identity

Bangla Press Desk: Expectations that extortion would decline in the wake of the events of 5 August have proved unfounded.

Far from easing, the problem has persisted – and in some cases intensified – despite hopes that a “new Bangladesh” would bring relief to public life.

Finance Adviser Salehuddin Ahmed observed, “Reaching a political understanding is very difficult, but reaching an understanding over extortion is much easier.”

He added that when one group of extortionists disappears, another quickly fills the void.

His remarks reflect a deeper reality: extortion has evolved into a strategic instrument for sustaining political power, not merely a criminal act.

Many expected the new administration to take firm action against extortion and establish transparent, accountable governance. Instead, the networks remain largely intact. Only the faces and political patrons have changed.

As one group falls, another emerges – underscoring that extortion is not confined to any single party but is embedded within the political economy of the state.

Media reports suggest that in Dhaka alone an estimated Tk22.1 crore is extracted daily from 53 transport terminals and stands – amounting to Tk60-80 crore a month. Nationwide, around Tk1,059 crore is illegally collected each year from the bus and minibus sector. Wholesale and retail traders also face daily, open extortion backed by local politics and various “organisations”. Refusal to pay brings threats of disrupted supply, forced closure, or direct violence.

Politically backed extortion is also rife in government and private development projects, construction, tenders, water bodies and sandbank leases. According to Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), between 2009 and 2023 an estimated US$13-24 billion (Tk1.61-2.80 lakh crore) from the Annual Development Programme (ADP) was lost to corruption and extortion.

A review of recent incidents shows five groups are now directly involved in extortion: first, individuals linked to political parties; secondly, sections of law-enforcement agencies; thirdly, certain members of the administration; fourthly, organised criminal groups; and fifthly, independent extortionists acting alone.

Extortion carried out under political identity or protection is currently the most widespread. Over the past 15 months, media reports have documented 2,325 extortion cases involving leaders and activists of various political parties.

Members of major parties – including BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami and NCP – as well as smaller groups have been implicated.

Several incidents have caused significant public outcry. Earlier this month, Shariatpur Super Service, which operates buses on the Dhaka Jatrabari-Shariatpur route, alleged that they were asked to pay Tk50 lakh per month in extortion. After refusing, several buses were vandalised, services were halted for several days from 8 July, and staff were assaulted. In protest, employees formed a human chain near the toll plaza on the Jajira side of the Padma Bridge.

The allegation was directed at a Jubo Dal office bearer in Jatrabari. On 12 July, the organisation expelled him and issued a press statement, warning that anyone misusing party identity for illegal activities would face action.

Over the past 11 months, BNP has expelled more than 4,000 leaders and activists over allegations of extortion, land grabbing and attacks. Yet the practice persists.

Similar allegations have emerged against Jamaat-e-Islami nationwide. In Taraganj, Rangpur, a land office assistant was filmed taking bribes; the video was later used for extortion. BNP blamed Jamaat for the incident. In Natore, locals staged protests against extortion by Jamaat activists. In Kazipur, Sirajganj, a businessman lodged a written complaint alleging that Jamaat workers demanded Tk10 lakh in extortion.

In Kumarkhali, Kushtia, Jamaat activists were accused of attacking a leaseholder at a bus terminal for refusing to pay. Police have since launched an investigation into allegations of extortion and attempted murder.

In Melandah, Jamalpur, a man posing as an official from the deputy commissioner’s office was arrested on 17 March for extortion. Police say the suspect, Sajjad Hossain Sakib, is the nephew of Jamaat leader Samiul Haque Faruqi.

In Lakshmipur, one Mehedi Hasan Tushar was accused of demanding extortion through threats of fabricated cases. He claims to be affiliated with Jamaat, though the party denies any link.

Multiple extortion allegations have also surfaced against NCP, the student organisation that played a prominent role in the July uprising. Several leaders have been arrested, criticised or investigated. Joint Member Secretary Gazi Salauddin Tanvir was temporarily removed from his post in April. Another leader, Abdul Hannan Masud, drew controversy after securing the release of individuals detained for last year’s mob attack in Dhanmondi. Since August, complaints have spread nationwide about the misuse of the “Coordinator” title for intimidation, extortion and lobbying.

In Chattogram, NCP’s newly appointed Joint Coordinator, Nizam Uddin, received a show-cause notice on 11 August over extortion allegations.

The NCP is now entangled in a growing number of such accusations.

Leaders of numerous smaller political parties have also faced repeated allegations – suggesting the practice has become almost routine.

BP/SP

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Death Threat Sent to NCP Leader Joynal Abedin Sisir on WhatsApp

-697fe5ecb751d.jpg)

-697f6373422df.jpg)

Courtyard meeting in Dhaka-17: Koko’s wife seeks support for Tarique